The Painter of God - The Timeless Art Master Max Liu

The ultimate mission of arts is not about aesthetics, but about love. --Max Liu

In 1911, a 7-month premature was born in the south of China. He had been feeble and lonely throughout his childhood. Exploring in the big garden of his family and the meadow nearby gave him the greatest pleasure. One time after the rain, he found a lot of little green frogs, greener than the grass…

“I’ve tramped and lain on many meadows and lawns, yet there is none as cool as this one; it is so charmingly green.” This nature-loving child was Max Liu.

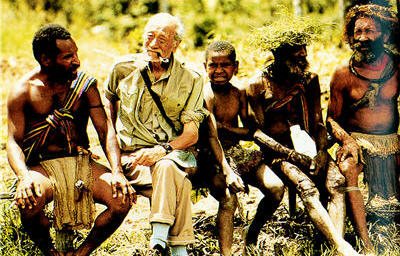

At that time he would never have known that he’d leave his hometown and endure a rugged journey through Japan, Yunnan and finally Taiwan, nor that he would undergo the 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and the Vietnam War. In his autobiography, he said “life is a challenge” and inspired the youth with a quote from Theodore Roosevelt, “Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die; and none are fit to die who have shrunk from the joy and the duty of life. Both life and death are parts of the same great adventure.”

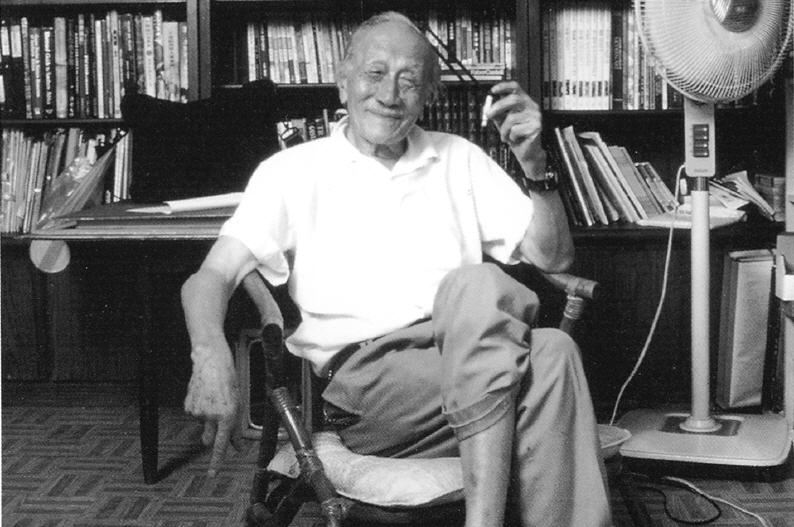

It was with this spirit that Max Liu, an “impish old man” as people called him, had lived his 91 years of life as a professional electrical engineer, to a painter, professor, anthropologist, and ecological conservationist.

Even with such a spectacular life, Max Liu was most proud of “being an honorary police officer of the national park.

Indissoluble Bond with National Parks

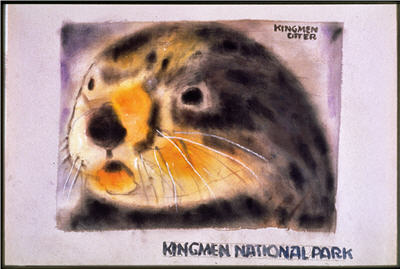

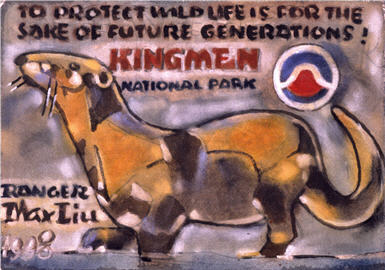

Liu’s bond with national parks originated in the “Yushan Movement”, co-hosted by the Yushan National Park, China Youth Corps, and New Idea Magazine in 1997. Since he had been dedicated to ecological conservation for years and preached related ideas with his vivid animal paintings, he gladly accepted the invitation to be the spokesman for the activity and the title of an “honorary police officer”.

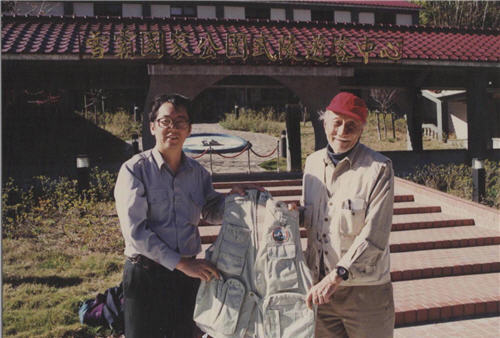

Afterwards, Kinmen and Shei-pa National Parks also invited Liu for a visit and offered him the honorary police position respectively. Yu-siou Li, then a docent of KNPH, recalled that Liu had accepted the invitation without a second thought about the long travel.

“He was very amiable. It was so delightful to be with him,” Li described this respectable old man.

Before meeting with Liu, Ming-yi Li, chief of KNPH, had only known him by Liu’s painting on her notebook’s cover. “I thought he was a very young man because his paintings look so playful.” And her first impression of Liu was: “just like my own grandfather yet with a childlike smile.”

Liu was deeply attracted to the relaxed and carefree living pace and beautiful environment on the islet. Once when he sat at the doorsill of an old house enjoying the sun, he asked Yang-sheng Li, then-director of the park, “Can I be a janitor here when I retire?”

Photographer/ Chieh-yang Su

Translator/ Chunyi Cheng

Photo provided by/ Prof. Shih-Tsen Liu

Special thanks to Prof. Shih-Tsen Liu, assistant professor of the Graduate Institute of Environmental Education, National Taichung University; Mr. Siang-jian Wu, deputy director of Yushan National Park Headquarters, Mr. Ming-yi Li, chief, Ms. Yu-siou Li, and Mr. Wun-wei Yang of Kinmen National Park Headquarters

Liu was also in love with the hospitable Kinmen people, and he returned them with two paintings of the Eurasian otter unique to Kinmen for the promotion of the park. “We gave him a volunteer vest and he’d worn it in many important occasions.” Li, now retired, still remembers Liu’s genuineness and devotion to the environment.

“Liu liked the soft and savory Kinmen peanut candy, because he could enjoy it merely with his gums, which he often boasted healthy.” Ming-yi Li remembers Liu’s laughing face and the faint tobacco smell so well. “I used to pity old men, but Liu’s utter innocence and ardor had great impact on me. He made me see that an old man can still do a lot and made me less worried but more confident about my own aging.”

The Old Painter Who Had Hunted Jackals

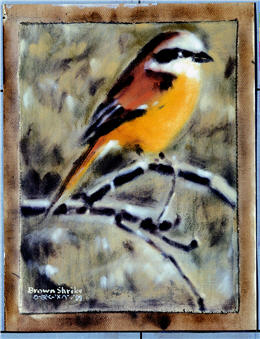

Siang-jian Wu, deputy director of Yushan National Park Headquarters, remembers his amazement when he first saw the series of animal posters made by Liu for the Council of Agriculture. “He caught the animal’s expression by a mere brush, as if he had known what the animal was going to say. Thus you feel his respect to the wild animals and his belief in preservation.”

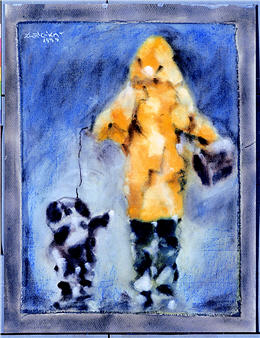

Because of this affection, in 1998 Wu invited Liu to see how Formosan landlocked salmon were restored and planted in Wuling area. Liu went up to the mountains on a cold winter day without a grudge, and his humor and laugh had again conquered everyone.

“I remember best that one time he asked us, ‘do you know the biggest advantage of eating vegetables? It is you wouldn’t need any tissue paper after a bowl movement.’” Wu said Liu’s jokes came from his understanding of life.

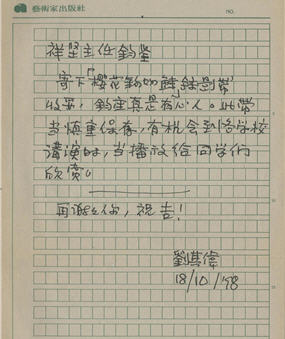

During his visit to Shei-pa, Liu was most interested in the work of a park ranger; he had talked a lot with A-jyu Lai, an Atayal ranger, whose main job was to remove hunting devices. After he left, Liu sent packages to the park twice. One was a down coat for A-jyu Lai; the other was 6 ingenious Swiss knives, the kind he took with him all the time to cut meat, for the headquarters staff.

Wu learned later that Liu had been a hunter, who had hunted jackals in Yunnan and boars in Taiwan. It was until one time after he killed a mother Formosan muntjac in his hunt and found that milk was still dripping out of the muntjac’s breasts, that he began to feel wrong about hunting.

delivered together with the Swiss knife and the down coat in 1998. The simple phrases were filled with infinite warmth./ Photo provided by Siang-jian Wu.

After reading Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Liu turned to advocate the living rights of wild animals and the preservation of natural resources. In 1976, he wrote an essay: “The Protection of Wild Animals and the Preservation of International Resources” published in Free Forum magazine. In the age when environmental awareness hadn’t burgeoned and hunting was still legal, this article was obviously pioneering.

Having put down the hunting gun, Max Liu began to write and paint, expressing his love and care for the nature through his creative works. The exploration in Africa, Borneo, and Oceania had infused more vitality into his thoughts and artistic creation, and the rippling power of his work has aroused the love from numerous people toward wild animals.

Animal Preservation is One Last Bit of Human Conscience

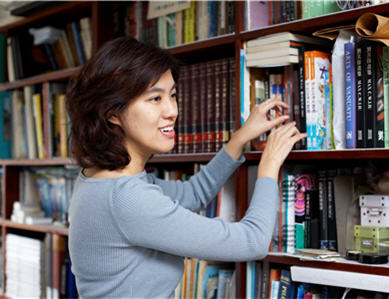

Liu’s love for nature has been passed down to his offspring; his two sons are both navigators, and his granddaughter Shih-Tsen Liu, now teaching at National Taichung University, has also stepped into the same field. She assists the Forest District Office to hold the “Max Liu Ecology and Art Exploration Camp” in Aowanda.

“The Lius all love animals,” said Shih-Tsen Liu, who had read a lot of books on ecology in her grandfather’s studio in her childhood. With a bachelor’s degree in business, she shifted to forest resources and agricultural and extension education when studying abroad. Before she went, Max Liu called her over to his studio. “He told me that to live is not easy, but we have to keep fighting. He even lifted his arms and repeatedly said ‘Fight! Fight! Fight!’”

In Ms. Liu’s memory, Max was not the kind of genial grandpa because he had seldom met with or greeted his family. He had been working all the time, painting, writing and planning his explorations, and even so on the day he passed away. He had led a simple but strict life. “It was all because of his willpower," said Ms. Liu, that he could have accomplished so much in his old age.

Liu himself once said, “I have not wasted a bit of my life.”

In the master thesis of Szu-Ting Chao, an advisee to Shih-Tsen Liu, the life and related information of Liu throughout his dedication to ecological conservation are recorded in detail. One simply would be moved by the efforts he had made late in his life to preach idea of environmental protection. Behind his bright and colorful paintings were an old artist’s great worries about the ravaged environment.

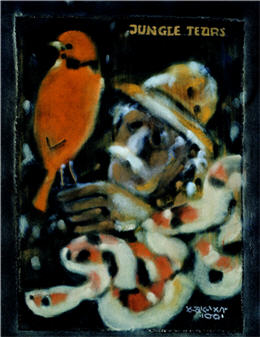

A good example would be Shih-Tsen Liu’s favorite painting of Max’s “The Hen Says: I Didn’t Know There Were Roosters.” Ms. Liu explains the title actually implies the fact that the hen has been confined all its life in the cage producing eggs without ever seeing a rooster. Liu also expressed his anti-nuclear stance in his paintings. In his painting “The Sorrowful Bird”, he wrote, “Bird eggs can’t hatch out because the earth is all polluted.” The expression was even more explicit in the “Furious Lanyu” series, where the staring eyes represent the fury of the Tao people on the islet.

Max Liu once said, “Animal preservation is one last bit of human conscience.” In his self-portrait “Stop Killing,” he showed repentance toward his past act of hunting and called for stoppage of illegal hunting. In “Gray Heron”, it is written “Save wildlife, save himself.”

Shih-Tsen Liu thinks that her grandfather had fulfilled an artist’s social responsibility through his art work and his own charisma. This also teaches us that everyone, no matter in what profession, can do something for the environment.

Szu-Ting Chao wrote in her thesis, “Max Liu demonstrates his ultimate concern toward the creation with true humanist spirit.”

Max Liu had respected life, and spared no effort to live his own, influencing numerous people around him. He also turned his love toward the world into bright-colored works which stay everlastingly in viewers’ hearts. Still, how much we miss the tenderness in the old man’s eyes and his childlike smile!