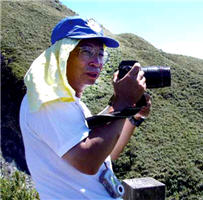

Among the many scholars dedicated to bicological conservation in Taiwan, Prof. Ying Wang is an influential figure who was born in Hangzhou, grew up in a military dependents’ village in Songshan, Taipei, and has long been devoted to wildlife conservation across Taiwan.

Wang has been known not only as an outstanding scholar in academic research, but also as an earnest mentor who has educated numerous talents about conservation concepts and learning attitudes. Many of his students have become the elite in the field of zoological studies in Taiwan and in Taiwan’s national parks today.

50 years ago when the communities near Songshan Airport were among rice paddies with all the fish, crayfish, frogs and snakes, Wang has started his exploration on living creatures in his hometown as a fenceless museum of natural history.

“I’ve been so into animals since I was little. I’ve always loved to watch them, and been lucky enough to have my education and career related to animals,” said Wang, who spent a wonderful childhood in the rural village and the open fields. To him, everything that crawls, swims or flies could be an interesting subject to explore.

“My childhood experiences have shaped me into a person who always loves to explore new life forms. I still have a lot to do even after I retire.”

Despite years of study in the U.S. before he obtained a Ph.D. in wildlife biology, Wang still has a special and strong bond with this homeland where he had been nurtured.

Though a Hangzhou-born mainlander who speaks limited Taiwanese, the congenial Wang was hardly hindered by the language barrier, but got along with people so well that he conducted research in Sheding at Kenting National Park (KTNP), Cigu lagoons at the Taijiang National Park (TJNP), Dafen at Yushan National Park (YSNP), mountains in Taroko National Park (TNP), and even in many remote aboriginal villages, where he always showed respectful and caring manners to local customs and people.

Since his return from the U.S., Wang spent nearly 30 years in the restoration of the Formosan Sika Deer (Cervus nippon taiouanus), which he thinks would reflect how well Taiwan do in wildlife conservation. If people could not become informed and take action to protect the environment, there’d be no future for conservation.

Back in 1980, the number of the sika deer in captive was about tens of thousands, but that of wild sika deer was almost nil. So Wang has been concerned about helping the deer live in the wild again. “The then-Director-general of CPAMI Mr. Lung-sheng Chang had the vision that the restoration of the endangered sika deer could raise people’s awareness in environmental protection and conservation,” recalled Wang.

Interview & Text/ Jane Chiu

Translator/ Kuan-yu Ou

Special thanks to/

Ms. Chia-chi Wang of the Planning Section at YSNP Headquarters

Mr. Ming-tang Shiao of the Conservation Section at SPNP Headquarters

Ms. Li-min Yin,an interpreter of YSNP Headquarters

Liang-li Liu,Prof. of Dept. of Tourism and Hospitality of Kainan Univ

Mei-hsiu Hwang, Asso. Prof. of Dept. of Wildlife Conservation of Nat'l Pingtung Univ

But this mission has been an uphill fight. “In addition to choosing the appropriate environment and deer for breeding and the proper transportation to release the deer to the wild, we also had to constantly communicate with local residents about the concepts of conservation.”

Indeed, apart from the difficulties posed by the conditions of environment and facilities, the biggest challenge came from people. Traditionally, local residents had seen the sika deer, whose wild release areas overlapped with where the locals herded livestock, as a resource for hunt. This had put the deer and the restoration of them in great danger. In order to solve the conflict arising from lack of understanding, Wang and KTNP Headquarters had continued to communicate with the locals. “Conservation is a dynamic process of putting research results into action.” That’s what Wang has been teaching his students and has been carrying out personally.

Often calling himself a “savage” in front of his students, Wang also wants them to be one when they conduct research in the field. Wang always takes students into the deep mountains and remote waterways to trace the Formosan Black Bear (Selenarctos thibetanus formosanus), observe the Brown Dipper (Cinclus pallasii ), and study the Formosan Sambar Deer, etc. while giving them much freedom and space to find out the answers by themselves

To Wang, only when humans see themselves as part of the Nature can they truly merge into it and feel it, just like other animals do. This equality is indeed a blessing for humans. But it also requires open-mindedness on students’ part to savor this “blessing” instead of seeing wildlife field research as drudgery.

The subjects of Wang’s teaching and research in the wild have mainly focused on birds and larger mammals. In the late 1980s, he had led his team into YSNP to investigate muntjacs, wild boars, black bears, sambar deer. “Due to the restrictions on tranquilizer guns back then, students had to set up traps to catch those wild animals, and place the radio transmitters on them.

They also needed to collect animal hairs or feces, record bird sound, and use infrared cameras and other equipment to study and analyze the animals’ behavior, population changes, and their impact on the environment.” More importantly, Wang also hopes students can be “well-rounded by learning to getting along with aborigines and understand their cultures and lifestyles.”

As Wang has been fighting for the environment and the “sustainability” of all life forms, he also selflessly strives for the “sustainability” of future talents in the field of biology and wildlife, and instills his passion for the Nature into them, among whom are quite a few staff members of Taiwan’s national parks.

Chia-chi Wang of the Planning Section at YSNP Headquarters, who grew up in the cities but had a special bond with Mt. Jade, was first introduced to a unique backpacking field trip of wildlife research in the wild at Walami as a college senior in 1997. “I had very limited mountaineering experience before I joined Prof. Wang’s team. I can still remember the way I exclaimed when I spotted Swinhoe's Blue Pheasant (Lophura swinhoii ) at Walami for the first time in my life!”

She’s also impressed by Prof. Wang’s teaching style. Strict in self-discipline but gentle in personality, he always initiates interactive heuristic dialogues with students and never tires of long or late-night discussions. “Prof. Wang would urge us to raise hypotheses on animals’ behavior, while playing videos of such topics during lunch break or taking the class to Wulai to record how the Plumbeous Water Redstart wags its tail. Most students would find his classes and overtime teaching truly worthwhile, perhaps except those who are already late for their date!”

Prof. Wang always takes the trouble to “move” the classroom to the wild, leading students to places like Huangdidian in Shihding or hilltop pavilions at Mt. Keelung in Jiufen. From the north to south to east of Taiwan, in each of the “classroom in the wild,” students follow Wang and cultivate sincere passion for the Nature.

Ming-tang Shiao of the Conservation Section at Shei-Pa National Park Headquarters, a relatively newer student of Wang’s, identifies with Wang’s philosophy to adapt to the changes of the research environment aside from counting on modern equipment. Shiao is also impressed by Wang’s constant curiosity and flexible thinking. “He’d want us to do observations in hot pot restaurants to see what kind of person would sit in which seat and choose what kind of food, and so on. Humans are animals, too, and this training has made ethology much more interesting than going through textbooks.”

To his comfort, the north side of the Lake is still underdeveloped, where over 700 Gray-baked Starlings (Sturnus sinensis) have chosen a gigantic banyan at a sheepwalk as their habitat. Liu hoped that “once migratory birds choose a fixed habitat in Taiwan, it means this island has some great places to visit with friendly humans and ecological environment.”

“You know what? At nightfall in October every year, numerous Gray-baked Starlings would gather up on the electric wires near the banyans. When they fly up in flocks, it's truly spectacular. And by looking up to the sky on the main street in Kenting, you can always spot egrets migrating 24/7 right above your head!” Liu's enthusiasm in introducing all his feathered friends is just as sincere, natural, and touching as those lively birds in KTNP.

In final exams, Wang would also ask students to design research questions from opposite perspectives, prompting students to actively pose questions and hypotheses. These have shaped Shiao into a researcher and a civil servant in the national park who’d always be at ease with all kinds of difficulties, all thanks to the tough training given by Wang.

“Honestly, the list of what I’ve learned from Prof. Wang is endless.” Shiao was particularly touched by Wang’s support to students. “There’s once when a student drove Prof. Wang’s car and had a nasty bump that cost NT$100,000 for repair. Prof. Wang didn’t blame the student at all but consoled him, saying: ‘Just think of it as a satellite transmitter gone with the animal in vain. It happens. That’s how life is.”

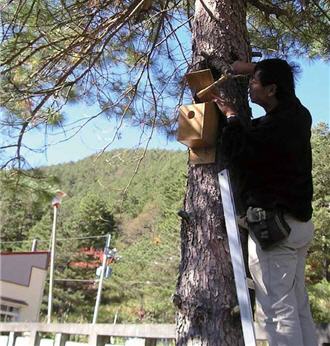

When Shiao once conducted an investigation in TNP as a Master student but the ladder for field research was too old for use, Wang looked through one hardware store after another for a new one, and drove all the way into the mountain just to send it to Shiao. But on Wang’s way back from the trip after observing nest boxes in the woods, Wang fell and broke four of his ribs.

“We went to visit him in the hospital, and he only hurried us to go back for study rather than waste time on him.” All those moments and words may be seen as trivial and unimportant to Wang, but will be remembered and cherished by his students for a lifetime.

“How much influence a teacher has had on his or her students can be reflected by how much students remember about him or her,” smiled Li-min Yin, an interpreter of YSNP. “After so many years, in each of our college reunion, we talk about nothing else but Prof. Wang.”

The way Yin became one of Wang’s assistant was unique because she used to be a history major but opted for a totally different career path by applying for the position as an assistant for Wang. And her enthusiasm for the Nature had won her the opportunity to work for him.

With Wang’s encouragement and support, Yin got the chance to go into the aboriginal villages, and know about their hunting traditions and their cultures that she has truly enjoyed. “I always think that had I not met Prof. Wang, I could be just a journalist and never be able to do what I really love to for a living,” thanked Yin. “Prof. Wang opened an important window of my life.”

Liang-li Liu, Asst. Prof. of Dept. of Tourism and Hospitality, Kainan Univ. and a student interpreter of YSNP, had also been a student under Wang, and impressed by Wang’s American teaching style that stresses students’ independence in planning, experimenting and problem-solving. “Students who actually learned from and survived Prof. Wang’s rigorous trainings all have some achievements in different fields.”

Strict as Wang is, he has never been stingy on the project budgets or research grants for students. He always offers as much financial support as he could to those students in need.

Liu described Wang as “an adult lion that throws its cubs to the bottom of the valley and watches them climb up while giving them due care and support in a strict but gentle style; he always acts both as a teacher and as a friend to his students.”

“Prof. Wang treats his students as his own children. He eats what students eat, never gets condescending, and always cares about students in all aspects. As his student, I felt so surprised but also delighted by all this.”

So observed Asst. Prof. Mei-hsiu Hwang, also known as the “Formosan Black Bear Lady.” In 1992, thanks to Wang, Hwang was involved in a campaign of releasing the cubs of black bears in TNP, and had her first contact with the black bears.

From research projects, meetings to field trips, Wang always provided Hwang, just a sophomore back then, with opportunities to get involved. He led her to Walami Trail in Yushan and Heping Logging Road in Taroko, and even bought her the flight ticket to the giant panda research center in Chengdu, Sichuan. What Wang had offered contribute to the most important turning point in Hwang’s research career. “Prof. Wang is an expert on black bears as well as a mentor who ushered me to the conservation work of black bears,” thanked Hwang.

This is what Hwang thinks the current competitive academia in Taiwan has lost and neglected. “When teachers only care about the amount of their publications rather than inspire students to learn, then education becomes meaningless.”

Wang has also been like a beacon that Hwang would consult whenever she feels frustrated in her research work. “Prof. Wang is like a kaleidoscope full of creative ideas and insights. He once told me there’s no absolute right or wrong for many things, especially in research or conservation, which require the cooperation of many factors. He always tells me: ‘just do your best.”

“Do your best.” Well said, indeed.

For Wang, whether or not he will retire someday or remain as energetic as the young researcher he used to be, he’ll never stop giving every bit of his efforts to the welfare of wildlife and to Taiwan’s wildlife conservation.

Wang has been concerned about many wildlife species endangered by humans’ modern civilization and technology. “It’s true that some wild animals are of great economic value for humans. So when it comes to the conservation of wildlife, we must develop a mechanism to both protect them as species and reasonably use them as resources.”

Wang explained that when wildlife are more abundant, such as in some developed western countries, it means animal resources are better managed. That is, with effective management, protected species can continue to exist without expanding excessively in number to become overly dominant.

“Before 2004, I had once borrowed similar experience abroad, and proposed a trial hunting system at Danda, Nantou County, hoping to make legal hunting a means of effective management of wildlife resources.”

Once a species overpopulates, Wang explained, legal hunting at designated areas and time and with certain quotas can be considered a win-win solution to not only bring in tourism revenues for the locals but prevent wild animals from becoming endangered by excessive illegal hunting.

Just as “a kaleidoscope full of creative ideas” as his students describe him, Wang believes there shouldn’t be just one fixed path for conservation work. More adaptive options can be found through multi-faceted discussions and analyses.

“I once came across a gem-faced civet on a tree at Dafen in YSNP with just one feet away from me! And also a muntjac in Fu-shan Botanical Garden, and a sambar deer in close distance in Mt. Panshi at the east hill of Mt. Qilai.”

All these encounters with wildlife are the results of more than two decades of habitat rehabilitation and improvement for numerous wild animals achieved by Taiwan’s national parks.

“Though ideally all species should be treated equal in conservation work, we couldn’t but put some particularly rare and endangered species as top priority for conservation due to the level of urgency.” But take Formosan Black Bears, the largest mammal in YSNP, for example. As long as the living environment of this wellknown species is well protected, it means the entire system for all other animals is, too. When this interrelationship among different species is understood, people will no more suspect the so-called “inequity” in wildlife conservation.

From sika deer, black bears, to black-faced spoonbills, Wang has never stopped his devotion to Taiwan’s natural environment. He has planned to help promote the resource management program in aboriginal areas in Danda after his retirement, with the hope of creating a close contact experience with wild animals for urban tourists while instilling the concepts of environmental education in order to raise their awareness in conservation.

Someday, maybe what Wang has envisioned would come true, when all kinds of large animals will be seen everywhere in the forests, indicating the abundance of wildlife resources that exist far beyond conservation areas.

For full-length texts of this article, go to the website of National Parks of Taiwan at: http://np.cpami.gov.tw/.

With a Ph.D. in wildlife zoology at the Ohio State University, Wang is currently a Professor of the Dept. of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University. He specializes in wildlife zoology and behavioral ecology, and has long been dedicated to the research and restoration of Formosan Sika Deer.