On September 10, 2011 at the Xuejian Recreation Area in Shei-Pa National Park, a unique fashion show titled The Heart of Forests – Atayal-styled Apparel: Weavings of Dancing Colors , was staged in front of an audience of over 2,000 tourists and officials.

With four major themes of traditional style, pattern prints, colored linen, and hand-woven clothing, the show perfectly blended Atayal weaving tradition and modern design in a marvelous presentation of artistic creativity in the colors and textures of Atayal apparel. And the heroine behind this fashion show was an Atayal weaving artist Yuma Taru, the founder of Melihang Workshop of Atayal Dyed Weaving Culture Park.

The half-Atayal and half-Han Yuma used to be a civil servant in the city before she returned to her original village by chance at the age of 29. She started to learn Atayal weaving techniques from her grandma, and felt a strong urge to revive this Atayal tradition in view of a worsening lack of tribeswomen who still possess the skill.

Yuma spent 3 years visiting over 200 villages to learn from the seniors; later, she was admitted to the Graduate Institute of Textiles and Clothing at Fu Jen Catholic University, and obtained her Master’s degree with a thesis about Atayal traditional textiles.

Afterwards, having quit a stable job as a civil servant, she recruited some “dream weavers” and moved back to the tribe to pass on the art of Atayal dyed weaving. In a span of over 2 decades, she has established the Atayal Dyed Weaving Culture Park, which consists of a textiles research center, Melihang Workshop, a botanical garden and a museum (now as a kindergarten).

According to the Atayal legend, only those women who know how to weave could have facial tattoos, a passport to pass the“rainbow bridge” after death and meet with the spirits of ancestors. The life of an Atayal woman is closely linked to weaving: She needs to learn to weave her skirt at the age of 13 or 14, her wedding dress at 17 or 18, the clothes for the entire family after she gets married, and her shroud for her own funeral when getting old. Her life is indeed interwoven with textiles and the art of weaving.

Interview & Text / George Sheu

Translator / Kuan-yu Ou

Special Thanks to / Technical Specialist Hui-fong Liu of SPNP Headquarters、

Baunay Watan, Cultural Documentary Director

“There is something deep and profound in the Atayal culture. To promote it, you must find the essence and ponder over it, not just play on the dazzling and superficial part,” said Yuma.

At first, Yuma used the usual ready-made thread for practice, but her grandma kept telling her: “This is not weaving.” This confused Yuma because she had been trying hard to weave the way she was taught. It turned out that in Granny’s mind the real weaving must include the use of and even the planting of the traditional material: ramie. So Yuma learned to look deeper into weaving and all things in life with introspection and changed the way she sees and does things.

Therefore, Yuma started to look around Taiwan for red ramie, the long-lost traditional material used for Atayal weaving. It took her a long while before she finally found a red ramie garden in Wufong County, Hsinchu. It belonged to an old lady in her 80s, who was willing to give all the red ramie toYuma for free as long as Yuma promised to continue to grow the ramie and pass it on to others.

It seemed like a destiny that someone had been guarding this last piece of a vanishing tradition, waiting for the coming of Yuma to inherit it with her strong sense of mission.

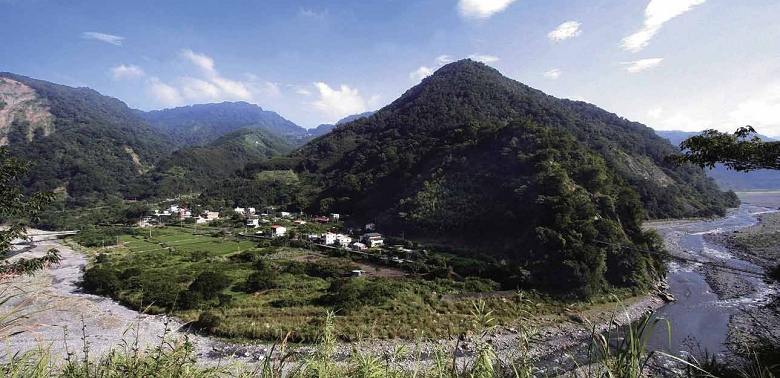

Yuma then came back to her hometown Xiangbi Community, where she began to grow ramie as threads and Shoulang yam (or kmages) as dyes. Step by step she restored an authentic environment for Atayal weaving and preserved the whole process of the tradition because Atayal weaving is the carrier of its culture and closely connected with the life ofthe Atayals.

But later Yuma encountered a bottleneck due to some limits in weaving techniques posed by current Atayal tradition, or GaGa . So she decided to find out the originality of even earlier Atayal weaving traditions through comparing with the weaving techniques of other countries in a scientific way. Over the past 20 years Yuma has categorized the Atayal weaving into 6 major parts: style, color, texture, print, technique, and history.

When the origin and the real beginning are found, everything becomes clear. Just like a kung fu master who, after realizing the essence of martial art, is empowered to fight his enemy with anything at hand, now under the leadership of Yuma, Melihang Workshop has produced quite a few modern textiles by using materials including not just the red ramie but also metallic, industrial-functioned, wicking, or elastic fabrics, or even optical fibers or LED (lightemitting diode), anything linear in nature. Various kinds of tools are used, too, to create fiber artwork and textiles for daily use.

Yuma has visited numerous villages of the Atayal tribe and overseas museums, where she saw over 1,000 of woven articles left by Atayal ancestors, including those made in 18th or 19th century and those before the Atayal started to use non-woven fabric. Many of the textiles had been collected by foreign scholars or visitors, and now could only be seen in various museums abroad.

By scientific exploration, compilation and analysis and research, Yuma has understood the basis of traditional Atayal weaving and figured out the corresponding applied techniques, through which she reproduced various traditional Atayal textiles and apparels that had disappeared or been lost for 80 or 90 years.

However, to many Atayal seniors in their 70s or 80s, who are younger than those interviewed by Yuma during her field research 20 years ago, these reproduced textiles are simplynon-existent. “Many of these seniors were brought up in the era of Japanization, and have never seen any earlier relics of Atayal traditional culture, including apparels and textiles,” said Yuma. So they reject what Yuma has been doing as something of her own creation, something non-Ayatal.

This prejudice has been frustrating as Yuma works hard to promote the tradition of her own tribe.

The biggest challenge along her fight for the renaissance of Atayal weaving culture, she said, comes from people. How to communicate with people, particularly those of her own tribe, has become the most difficult task because they don’t understand her work and her aims. Yuma has been frustrated by this and even misunderstood by her closefriends. “Well, a strong sense of competition is also part of Atayal tradition, especially in the aspect of skills,” she said.

These years Yuma has achieved some success and thus some fellowmen in her tribe started to take a defensive stance against her. She was even rumored by people of other tribes as a witch and a copycat that’d steal other’ sideas and skills altogether.

“Learning a technique is much easier than communicating with people,” she lamented.

What, then, has been the driving force that supports Yumain continuing such a difficult job? It is the care and warmth given by those nice seniors she had met during her field research in her younger days.

Despite an Atayal tradition that a mother passes on weaving skills only to her daughter and never to someone outside the family, those open-minded seniors were so glad to see a young tribeswoman fully committed to promoting the Atayal culture that they did the utmost to teach Yuma everything they knew.

Yuma has always kept in mind their support, and vowed to pass the torch of traditional Atayal culture.

In Yuma's mind, traditional textiles and modern textiles are not that different. Basically, modern textiles or modern public art starts from materials, and the feel and presentation of different materials are closely associated with tradition.Tradition is the basis and source of modernity.

Yuma sees what she’s doing as a process of translation, and herself as a translator of culture who transfers the essence of tradition into something that could be appreciated by people, just like a translator of language who renders Atayal into Chinese or English.

To create by adding something new to the tradition is what every creative artist pursues. This spirit is particularly manifest in Yuma, and is the source of her diverse creations.

There used to be certain taboos for traditional arts and skills. Atayal weaving, for example, was definitely not for men. But Yuma would teach men about weaving if they want to learn. “Men are actually fitter for modern and large-sized weaving,” she said.

As for how to strike a balance between following the tradition and breaking it, Yuma thinks that one should grasp its essence and spirit but get rid of its form and rules. “Tradition is solemn and respectable, but a true artist should not blindly follow it or copy it but must know what he or she is doing.”

That’s how Yuma has shown her creativity, pragmatics and consistency in many things.

In the box-office hit Seedig Bale, more than 1,000 Seedig garments worn by the actors and actresses were made by Yuma’s Melihang Workshop. It’s not about making money but supporting a film that tells a meaningful story related to her own tribe, the Atayal. Yuma and her weavers had spent 2 months churning out all the clothes with a disproportionately low charge. They are what the movie’s director Te-sheng Wei called “angels” that he truly thanked for their help.

And the fashion show The Heart of Forests has entered its fifth year, something Yuma sees as a long-term craft movement rather than just a display or a commercial activity. It is through this fashion show of both traditional and modern elements that Yuma hopes to allow younger generations to understand her works and ponder over the tradition, and most of all, interest them in grasping the ideas of cultureand generating their own thoughts.

What Yuma has been considering about traditional Atayalweaving is not just the acquisition of the skills but thecontinuation of the tradition.

“I believe the Atayal ancestors did have many traditional wisdoms, but it’s a pity that many have just become superficial items such as stickers and souvenirs,” said Yuma.

“Maybe in 10 or 20 years of time there’ll be no ‘real’ aborigines in Taiwan but only some partially aborigine-blooded plainsmen who wear like indigenous people. That’s why I decide to revive aboriginal education to preserve the essence of the Atayal culture in the inner of people insteadof on the appearance so that there’ll be fewer people who only present shallow forms of aboriginal culture, and try to interpret Atayal traditions with partial knowledge of them.”

Yuma believes that the key to the survival of an ethnic group lies in its “people.” It takes wise, talented and ambitious tribesmen to inherit and pass on its culture and save it from vanishing. “Only through education can the tradition and culture of a tribe be truly restored and valued by its people.”

“I can dedicate myself to this for 50 years,” she said.

Since her return to her village, Yuma had spent the first decade in field investigations, searching for the Atayal weaving tradition, and the second decade in training weavers. She’s now heading toward the next 30 years, inwhich she will found schools for Atayal fellowmen, first an ethnic kindergarten and then an Atayal dyed weaving craft school.

She hopes to build this ethnic school inside the village, with emphases on specialty and depth, and could someday attract the best craftsmen worldwide for exchange like some foreign professional schools do. Admitting 10 to 15 students a year would suffice, and the school would provide board and lodging for those who have interests and imagination in Atayal weaving.

Many have questioned Yuma: “Where are you going to get the land and the fund for setting up the kindergarten and the weaving school?” But she wouldn’t mind. Some willing teachers and a humble shanty were all she needed.“Just like how we started Melihang Workshop, it all began in a simple cottage,” said Yuma.

And she never worries about the money when she strives to realize her dreams. “I just want to do this” is the only thought on her mind. Then she would just do it step by step, little by little. Through collective work, she believes, more and more forces and resources would accumulate into fruits over time.

What Yuma wants to do is not just some short-term projects but something meaningful for the next 50 or 100 years and beyond. With such an explicit goal in mind, she has been sparing no effort in establishing the school that would still thrive 50 years later in preserving the Atayal culture. From setting up the workshop, training weavers, writing books to recording data, all she has been doing are building up toward the founding of this weaving school.

For the past 20 some years Yuma has worked 18 to 20 hours a day almost without taking any days off. “I am a person who lives on her dream!” the strong-willed Yuma joked. To Yuma, her dream is what has been driving her forward and supporting her along the way however difficult the road was, is and will be.

![]()

Born in 1963, Yuma is an Atayal with a Han Chinese name “Ya-li Huang.” Cultivated in the Han Chinese education system, Yuma obtained her Master’s degree at the Graduate Institute of Textiles and Clothing at Fu Jen Catholic University. She had once worked as a civil servant and a junior high school teacher. During her job at the local textiles exhibition hall in Taichung County Cultural Center, Yuma started to connect her selfdeeper to her roots and the Atayal culture, and later headed toward the road to the renaissance of Atayal weaving.