Towering at an altitude of 3,952 meters, Yushan is a mountain sacred to both the Bunun and the Tsou. According to mythology and legends, the Bunun and the Tsou people were not the only ones lived at the foot of Yushan or took refuge in Yushan during the Great Flood. They shared the mountain with the Saaroa, the Mumusu, the Bantalang, the Maya and other ethnic groups.

The Bunun people calls Yushan “Usavih,” and the mountain ranges “Saviq.” It was the mountain where the Bunun took refuge during the flood. The Tsou people calls Yushan “Patungkuonu,” which refers to Yushan and the Batongguan region. Thus, not only do ethnic languages impart ancestral wisdom, but also demonstrate unique geographical meanings that can be traced to their history and culture.

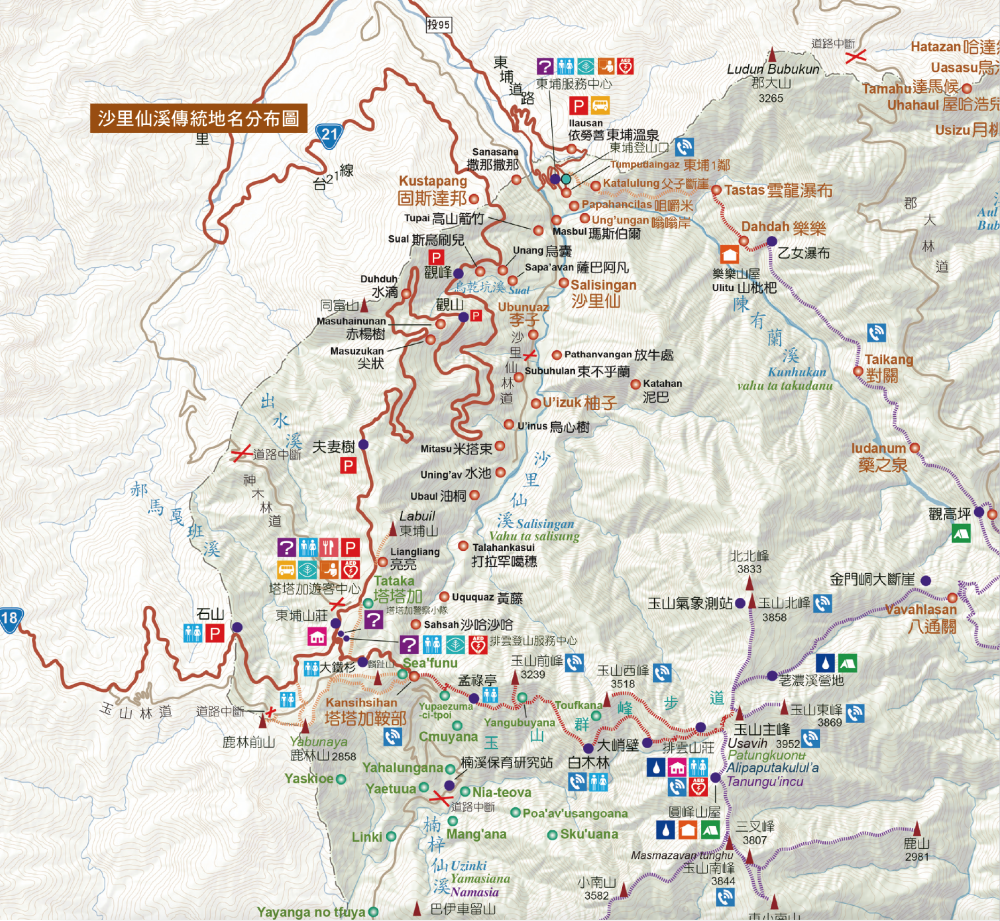

The traditional names of places are an important medium for emotional connection between people and the locale, reflecting the surrounding geographical environment and human activities during various times. In 2021, the Yushan National Park Headquarters initiated the “Survey Project on Traditional Names and Cultural Meanings of Indigenous Regions in the Yushan National Park,” inviting Professor Haisul Palalavi of the National Taitung University to conduct field surveys and interviews. The research data has since been compiled and incorporated in Languages of the Mountains and Forests.

Professor Palalavi, who is a Bunun and proficient in the Bunun language and culture, is the first ethnologist with a doctoral degree among the indigenous people. The Yushan National Park Headquarters’ survey project covered the entire park. Its objective was to trace the traditional cultural meanings of place names left by various indigenous peoples who once lived on this land.

Professor Palalavi spent two years working on this project, going through both the archives and oral sources, as well as visiting tribal communities within and without the mountains for investigating, documenting, and organizing his research. His endeavor is able to enrich the historic legacy of the indigenous peoples.

Professor Palalavi conducted interviews with tribal elders, as well as carrying out on-site surveys and archival collection to find out stories, mythology, and legends related to the mountains, hills, old communities, and cultivated land. He then “restored” the names of these places into the Bunun or Tsou language using the current pinyin method.

The Yushan National Park Headquarters pointed out that although some of the signboards in the park do include the indigenous names of the places and their pinyin to help with pronunciation, it is not always possible to understand the stories behind them from the Chinese characters or pinyin. Thus, Languages of the Mountains and Forests will help the public comprehend the true meaning of these names or stories. Many vestiges of old communities can be found in Yushan, leaving behind traditional place names with cultural and ecological significance. Thus, Languages of the Mountains and Forests is able to guide the younger generation to learn more about the indigenous history.

To provide readers with an easy and engaging reading experience, the book is presented in a storytelling style. Through systematic organization and a wealth of illustrations and texts, it is hoped that this publication will broaden the horizon of the public and provide people with new understanding of the Yushan National Park through details on history, ethnic groups, and their lifestyle.